This is Part 2 of a 15-page tutorial (in three parts) that will show you how to build an heirloom-quality, all-wood chess or checkers board with just a few small pieces of lumber. (Use the page navigation at the bottom of each post to change pages within each part.)

This part covers cutting the squares through planning this inlay. You can also:

- Go back to Part 1 (6 pages), which covers planning through first layer glue-up.

- Skip to Part 3 (4 pages), which covers cutting the inlay through finishing.

- See a gallery of reader-built chess boards here: Reader-built Chess Boards

Cutting the Squares

Now it’s time to cut the squares. Start by trimming one edge of the board so that it is perfectly perpendicular to the first slice you glued down. Take off only as much material as you need to make the ends of the slices flush with the edge of the board. I use a shop-made crosscut sled for this.

Next, measure the width of the stripes carefully, and add a stop block to the crosscut sled (or set your table saw fence) so that when you cut across the stripes, you’ll end up with pieces exactly the same width as the stripes themselves – 2 inches in this example. (See photo below.) Write the numbers 1 through 8 across one of the light stripes so you’ll know the order in which you made the cuts. You can see the numbers (albeit faintly) in the image below written on the second light stripe from the bottom. The numbers go from right to left. Measure again, take a deep breath, measure again, and then cut your first strip.

You’re going to be slowly cutting away at the nice long straight edge that you started with, so it’s a good idea to draw a reference line on the sled indicating the width of the pieces you’re cutting . . . better safe than sorry.

Be sure to check for sawdust next to the stop block between each cut. (See photo.) Dust and splinters here can result in unequal widths – something you definitely want to avoid when making a chess board.

Continue cutting until you have eight strips of the same length and width. Make the last cut carefully and use a ruler or the alignment line you drew onto the crosscut sled.

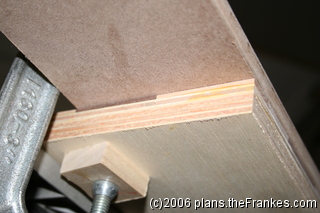

You’ll end up with eight pieces, each exactly two inches wide. Note in the photo that the backer board extends a little further than the walnut square. This is okay because it’ll be trimmed off a little later.

Orienting the Grain

Now you really get to check your work. Lay out the eight pieces and alternate every other one to get the checkerboard pattern so common on chess boards. 😉

This is the time when you need to make a very important grain decision: As you may already know, a chess board is correctly positioned when the white square is at each player’s right hand side. The way you lay the pieces out now will define which direction the grain will go – either player-to-player or side-to-side. It’s pretty common for the wood grain on chess boards to run across the board from player to player. For this board, though, I wanted to allow the grain to run across the board from each player’s left to right – to see if it might make me a better chess player. So, in the photo above you see the grain running from side to side with the white square in the lower right-hand corner. To orient the grain in the other (more traditional) direction, simply reverse each of the eight pieces independently. (It’s not good enough to reverse them all together as one, because you’ll end up with the exact same pattern.) To be sure, if you want a more traditional player-to-player grain, then the bottom right corner in the photo above should be black. Once you have the pieces oriented the way you want them, be sure they’re numbered clearly and draw arrows to indicate their orientation. You can see the arrows and numbers drawn onto the maple squares below. (Note that the squares are misaligned only because they haven’t been glued down yet.)

Second Layer Glue-up

Now cut a piece of half-inch plywood about the same size as the 1/4-inch piece you cut before. You’ll glue all eight sets of squares to this board in much the same manner as you did before, so be sure one edge is perfectly straight. All the other edges can be cleaned up later. Prepare each of the eight pieces by sanding them smooth on the bottom and cleaning off all the dust and splinters. I usually soften the bottom edges as well to allow a little room for the glue to squeeze out.

Again, use wax paper to protect the crosscut sled. Orient the new 1/2-inch backer board so that the grain is (again) perpendicular to the grain of the first 1/4-inch backer board. Clamp the backer board firmly against the edge of the crosscut sled, then glue down the first of the eight pieces. Pay careful attention to the arrows and numbers you wrote on the pieces during layout.

You’ll be adding some clamping pressure to the first piece you glue down, so wait a solid 24 hours or so for the glue on the first piece to cure completely before proceeding. You may need to clean up any glue that has squeezed out after you have glued down each piece. I usually do this with a sharp chisel. Do a dry fit before you glue down additional pieces to be sure there’s nothing that will keep the pieces from joining tightly.

Glue up the remaining pieces one by one, paying careful attention to the markings you made when you initially laid them out, and carefully aligning the black and white squares so they alternate. You want to be very accurate here to minimize alignment errors, but if you do find that the lines don’t quite “match up” on one end as they do on the other, then just position the piece to minimize this across the board. Tiny alignment errors won’t even be noticeable to most when you’re finished. When you’re finished with the second glue-up, you should have something that looks very much like a chess board!

Leveling the Top

Grab a pencil and scribble a bit in all the areas that are obviously low. The pencil marks will be a guide for sanding the top. You can see pencil marks in the photo below.

Next use a handheld belt sander to sand the surface carefully with 100 grit paper. Start by sanding across the grain, then along the first diagonal, then with the grain, then along the second diagonal. Cover the entire board with each pass, and be careful not to gouge the surface with the sanding belt. Alternating directions in this way helps to remove material (when sanding either directly or diagonally across the grain) and also minimizes the effect of simultaneously sanding species of different densities.

Your goal here is to just get a rough level – you’ll level it completely after the frame has been attached. When the pencil marks are gone, it’s close enough.

Cleaning Up the Edges

Now it’s time to clean up the edges. Start with the table saw and trim the backer boards until they are just slightly proud of the squares on the face. I typically “nibble away” at the edge so I don’t accidentally cut in too close.

Next install a pattern bit into your router. Using a straight edge, this will allow you to bring the backer board perfectly in line with the face.

Fasten a straight edge to the surface so that it lines up perfectly with the edges of the squares. Here I used a piece of MDF. Clamp it down securely.

Then use the router with the pattern bit to true up the edge. Use more than one pass if necessary.

You’ll end up with a perfectly clean edge.

Continue this for all the edges, checking for square after each cut. You may need to trim a tiny bit of the face squares if your glue-up wasn’t perfect, but don’t worry – a tiny bit like this isn’t going to be noticeable in the final product.

Planning the Frame

Select a piece of wood that’s the same thickness (or slightly thicker) than the chess board. I usually grab a piece out of the scrap pile that’s about the right size, and then cut it down to fit. I like to use the same species as the light squares, because I believe it makes the board look more elegant, but many boards use the darker species instead.

Here’s how to make a piece of scrap fit: If you’re working with a scrap board, it should start off longer than the width of the chess board (16 inches in this case). Measure the difference. You’ll either be limited by the length or the width of the board.

If the difference is, for example, 3 inches, then your frame (if with mitered corners) will be 1.5 inches wide, and your piece of scrap will need to be at least 6 1/2 inches wide (4 times 1.5, plus 3 times 1/8 to account for saw blade kerf, plus 1/8 inch for safe measure). If it is at least this wide, then set up your table saw to rip four 1.5-inch pieces from your scrap and number them consecutively.

If your scrap is not at least 6 3/8 inches wide, then you’re limited by the width of the board instead of its length. If you’re using a typical saw blade (1/8 inch wide) the, subtract ½ inch from the width of the board and then divide by four. So if the width is 6 inches, your frame will be 1 3/8 inches wide (6 minus 0.5 is 5.5, which divided by 4 equals 1.375). In this case, set up your saw to rip four 1 3/8 inch wide pieces and number then consecutively.

Arrange the frame pieces around the board until the frame looking just right, then label the label the board and the frame pieces with the letters A through D so you can match it up again easily when it comes time to glue. Here you can see I’ve written the letter A on both the board and the adjacent frame. We’ll be cutting the frame piece by piece to match the board perfectly, so you’ll want to mark exactly where the cuts should be. To do this, lay out the frame around the board so the boards overlap at the corners, as in the photo below.

Then draw a pencil mark exactly where the pieces overlap.

Now draw a reference line on the diagonal of the miter. If all goes well, this is exactly where your cut will fall, but consider it a reference line just in case. Mark all eight corners (both sides of all four frame boards) the same way.

Planning the Inlay

Next go back to your scrap pile and choose a several long, thin pieces of the other species of wood. These will form the inlay which separates the board from the frame. They need to be as long as the checkerboard is wide (16 inches in this case), but the width and thickness don’t really matter at this point so long as you’re a little flexible in your design. I’m a little nuts about saving scraps so I usually have a lot of long, thin pieces laying around for just this sort of application.

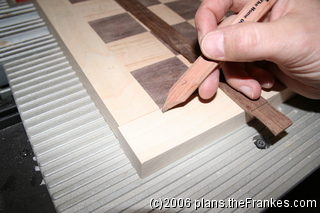

In the photo below, you’ll see that I have a long thin piece of walnut – just longer than the board is wide (16 inches), but still a bit shorter than the frame is long. This is okay because you’ll be mitering the corners of the frame.

I grabbed two such pieces, taped them down to my crosscut sled, and ripped them in half.

Note that the four pieces I ended up with are all slightly different widths and lengths. This is just fine, because you’ll be cleaning it up with a router for a perfect match.

This is the End of Part 2. You can:

That email directs to my phone, page 4 in the second section you wrote “No draw a reference line on the diagonal of the miter.” Im guessing that is supposed to be ‘now’.

Good catch — fixed it. Thanks!

Mixing up “now” and “not” — and now “no” — is probably one of my worst typos, resulting in things like “Great news! An updated version is not available!” Ugh… 🙂